Chapter 3: Introduction to Linear Algebra including Vectors and Matrices (Part 1)

1. Keywords

- Points, Lines and Planes

- Scalars and Vectors

- Vector Spaces

- Matrices

- Applications

2. Abstract

Abstraction plays a crucial role in bridging the gap between reality and mathematics by distilling intricate concepts into abstract representations. Through the use of matrices, vectors, scalars, and linear equations, we can manipulate mathematical objects in an abstract way, enabling us to explore and understand complex relationships in a structured and efficient manner. This interplay between abstraction and concrete application is at the heart of linear algebra and its pervasive influence across various fields of study. This chapter provides an introduction to linear algebra, focusing on vectors and matrices. It covers the fundamental concepts of vector spaces, scalar operations, line and plane equations, vector representation, matrix representation, operations, and practical applications in physics, computer graphics, data analysis, and signal processing.

3. Introduction

3.1. Linear algebra simplifies reality to models: From complex real objects to simpler linear equation modelsof variable relationships to still simpler vector and matrix representation

In essence, linear equations model reality by describing how things relate to each other, while vectors and matrices represent these equations as tools that facilitate their study, manipulation, and application in solving real-world problems. This duality highlights the complementary nature of mathematical abstraction and computational practice in linear algebra. The term “mathematical object” refers to any entity within mathematics that has distinct properties, can be defined or described using mathematical language, and often plays a role in mathematical reasoning, proofs, or constructions. Mathematical objects are abstract entities that exist independently of physical reality but are central to the study of mathematics.

In the realm of mathematics, abstraction serves as a powerful tool to distill complex concepts into more manageable and comprehensible forms. In other words, linear algebra involves the use of simpler mathematical objects (matrices and vectors) as tools to represent and manipulate in an abstract way other mathematical objects of interest (models of reality like linear equation). Here, ‘abstract way’ means that complexities which would make the mathematical object incomprehendible, are rendered vague or in other words the mathematical object is rendered into a simplified version of reality. Linear equations can exhibit both geometric and algebraic characteristics depending on the context and the variables involved:

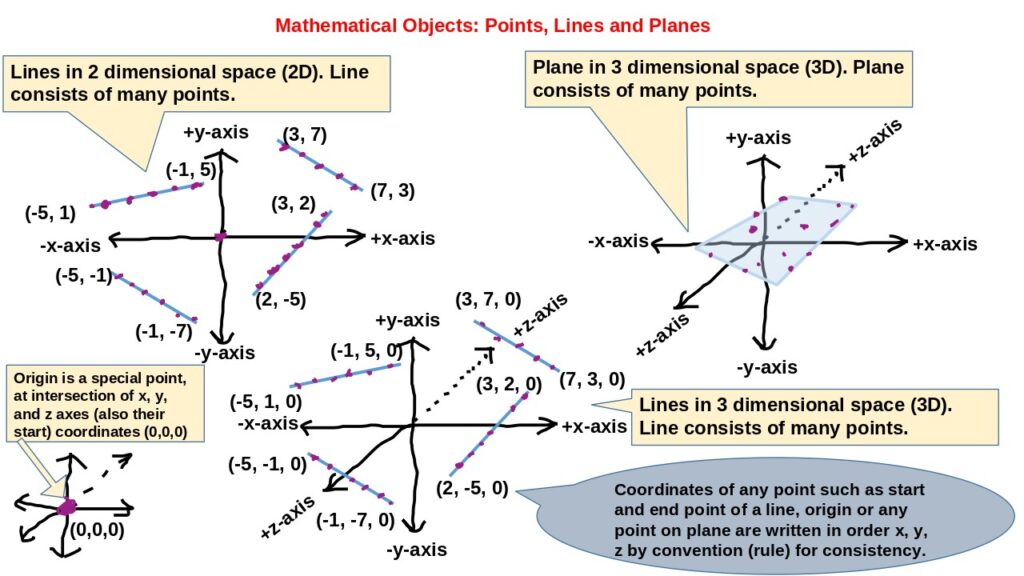

- 3.1.1. Geometric Interpretation (Geometry): Lines and Planes: In geometry, a linear equation often represents a line or a plane. For example, the equation 2x + 3y = 5 describes a straight line. The coefficients (2 and 3) influence the angle and location of the line, respectively. Similarly, an equation representing a plane might look like: x + 2y + 3z = 0. Points: Linear equations can also define points in space. For instance, the point (x, y, z) that satisfies an equation like x + y – z = 1 would be a solution point in three-dimensional space.

- 3.1.2. Algebraic Interpretation (Algebra): Relationships and Transformations: Linear equations model relationships between variables. For example, the equation y = 2x + 3 describes a straight line transformation where each increase of 1 unit in x corresponds to an increase of 2 units in y, with a starting point being (0, 3). Systems of Equations: Algebraic linear equations are often used to represent systems of equations. For instance, the system x + y = 5 and x – y = 2 would have solutions that satisfy both equations simultaneously.

The nature of the equation depends on the context and how the variables are interpreted. Geometry focuses on visual representation and spatial relationships, while algebra emphasizes abstract relationships between variables and their transformations. So, a linear equation can be considered geometric when it describes a line or a point in space, and algebraic when it represents a relationship between variables or solves a system of equations.

Vectors and matrices are essential tools in bridging the gap between geometry and algebra, especially when dealing with concepts like linear equations, lines, points, planes, vectors, and matrices themselves. Vectors and matrices play a pivotal role in connecting the fields of geometry and algebra by providing a common language and structure for representing and manipulating mathematical objects. Let me explain:

- 3.1.3. Linear Equations as Bridges: Linear equations, which are fundamental to both geometry and algebra, serve as a link between the two disciplines. In geometry, linear equations often describe lines, planes, or curves in space. By representing these geometric objects with equations, we can apply algebraic techniques to analyze and manipulate them. Similarly, in algebra, linear equations model relationships between variables, making it possible to use geometric interpretations to solve and understand these equations.

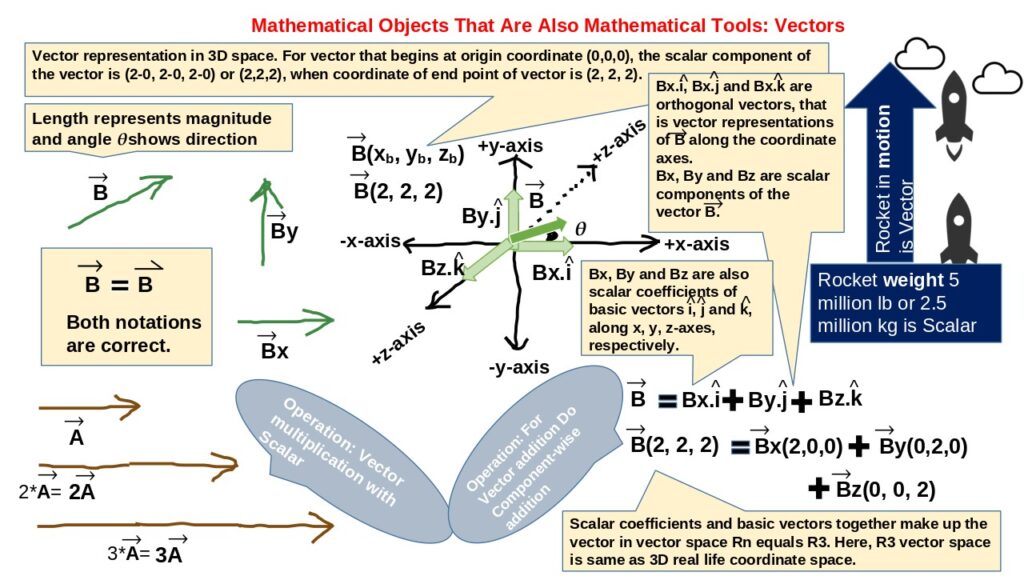

- 3.1.4. Vectors as Geometric-Algebraic Hybrid: Vectors combine the best of both worlds. In geometry, vectors have magnitude and direction and are used to represent changes or displacements in space. They help visualize and manipulate geometric concepts. Algebraically, vectors can be represented as column matrices, with each component representing a variable. This allows vector operations, such as addition and scalar multiplication, to be performed algebraically using matrix manipulations.

- 3.1.5. Matrices as Transformational Tools: Matrices are rectangular arrays of numbers that can represent linear transformations in both geometry and algebra. In geometry, a matrix can represent a rotation, reflection, or scaling transformation applied to points or objects in space. Algebraically, matrices are used to solve systems of equations, represent linear maps, and perform matrix operations. By applying matrix operations, we can transform one set of coordinates into another, connecting the geometric and algebraic interpretations.

- 3.1.6. Common Language for Geometric and Algebraic Concepts: Vectors and matrices serve as a common language that transcends the boundaries between geometry and algebra. They provide a unified framework for representing and manipulating points, lines, planes, and other geometric objects using algebraic techniques. This enables us to apply abstract mathematical concepts, such as linear algebra, to real-world problems in fields like physics, engineering, computer graphics, and machine learning.

- 3.1.7. Solving Complex Problems: The duality of vectors and matrices allows mathematics to be applied broadly. By translating geometric concepts into algebraic forms and vice versa, we can tackle complex problems that involve both geometry and algebra. This bridge between the two disciplines enhances our understanding and problem-solving capabilities in a wide range of scientific and engineering fields.

Thus, we realize that vectors and matrices are essential tools that facilitate the seamless integration of geometry and algebra. They provide a common framework for representing and manipulating mathematical objects. The utility of vector and matrix tools in representing and manipulating mathematical objects is especially apparent for mathematical object such as linear equation models of real-world. Taken together, this framework of real-word → linear equation model → representation and manipulation by vector and matrix tools, enhances our ability to solve complex problems and connect abstract concepts with real-world applications.

Abstraction (stripping off too many details) allow us to create a simpler model of reality (just the bear bones structure of reality) so that we can know reality and potentially change and predict reality. Linear equations exemplify this process by representing relationships between variables in an abstract manner, using mathematical objects such as vectors and scalars to convey these ideas. While reality may be perceived through sensory experiences and concrete observations, the mathematical world operates on principles that transcend physicality. Abstraction allows us to focus on the essential properties of linear equations—the way they relate variables, transform one into another, and maintain consistency across different contexts—without getting bogged down by irrelevant details. Representation in mathematics refers to the act of assigning meaning or form to abstract entities, enabling us to communicate and manipulate these concepts effectively. In the case of linear equations, representation involves expressing relationships between variables using matrices and vectors, where each element signifies a specific amount or direction. This abstraction enables us to perform operations like addition, multiplication, and transformation on these mathematical objects, which would be impractical or impossible in their raw form. The essence of this representation lies in its ability to encapsulate the fundamental structure of linear relationships while remaining adaptable to various applications across disciplines such as physics, engineering, economics, and computer science. Mathematical objects, such as vectors and scalars, serve as the building blocks within this abstract framework. Vectors, which can be thought of as directed quantities with both magnitude and direction, represent physical entities like forces or velocities in a linear system. Scalars, on the other hand, are simple numerical values that quantify these relationships. Through abstraction, we can manipulate these objects according to well-defined rules and operations, such as scalar multiplication or vector addition, without needing to understand their precise geometric interpretations. Mathematical equations, like linear ones, act as bridges between abstract representations and concrete applications. They provide a formal language that captures the essence of relationships between variables, allowing us to derive conclusions, make predictions, and solve problems with precision. In this sense, linear equations are not just mathematical constructs but tools that help us navigate and understand the world by translating complex interactions into simpler, abstract forms that can be systematically analyzed and applied.

3.2. Linear algebra is a cornerstone of mathematics with extensive rich history of discovery and innovation.

| 3.2. Clairement Explique: Discovery vs. Innovation: Similarities and Differences Both discovery and innovation involve exploring unknown territories, driven by curiosity and a willingness to take risks. They contribute to advancements across various fields such as science, technology, literature, art, and business. Discovery uncovers hidden truths, whereas innovation builds from scratch, creating entirely new concepts and driving progress through active experimentation. |

The tools (matrix, vectors, scalars) and their operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication) used in linear algebra on linear equations, were developed by several pioneers in history.

The development of vector algebra and matrix theory took shape much later. The concept of a scalar, a quantity described only by magnitude (e.g., mass, temperature), is arguably the most intuitive. The development of the vector—a quantity possessing both magnitude and direction—is heavily credited to mathematicians like William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865) and Hermann Grassmann (1809–1877), who sought tools to describe rotations and forces in 3D space. The formal theory of matrices was advanced by Arthur Cayley. Historically, the concepts that underpin vector and matrix algebra evolved gradually, often driven by the need to solve systems of linear equations or to describe physical phenomena like motion and force. René Descartes (1596–1650) laid the groundwork for modern coordinate systems, which are essential for defining space dimension. However, the formal history of linear algebra, dimensions, points, planes, lines, vectors, scalars, and matrix can be traced back to various mathematicians and scientists across different periods in time. For a more detailed understanding, here is a brief overview of some key figures involved in the development of these concepts: (Ref: https://en.wikipedia.org; Ref: https://www.britannica.com/)

1. René Descartes (1596–1650) – Developed modern coordinate systems that are essential for defining space dimensions.

2. William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865) and Hermann Grassmann (1809–1877) – Developed the concept of a vector, which is a quantity possessing both magnitude and direction.

3. Arthur Cayley (1821–1895) – Advanced the formal theory of matrices.

4. Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789–1857), Karl Weierstrass (1815–1897), and Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866) – Contributed to the development of complex analysis, which is essential for understanding vector spaces.

5. Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) – Developed concepts related to linear algebra in their work on differential geometry and number theory.

6. James Joseph Sylvester (1814–1897) and Camille Jordan (1838–1922) – Established the foundations of matrix theory through their research on linear algebraic invariants.

3.3. Linear algebra provides the mathematical framework for understanding linear relationships and transformations.

Linear algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with the study of linear equations, a kind of mathematical object, and linear equation properties, using mathematical tools of vectors and matrices. While scalars, points, planes, vectors, matrices and linear equations are all mathematical objects, they serve distinct roles. Linear equation serve as simpler models of complex reality, while vectors and matrices serve as tools to understand though change (operations or perturbation) and make predictions about the linear equation model, and thus by extension about reality.

If mathematics is analogous to a vast library containing multiple sections, then linear algebra would be one of the sections specifically focused on rules and methods for studying straight lines (linear equations). Matrices, vectors and scalars are tools of linear algebra used to represent linear equations. Ergo, when matrices, vectors and scalars are changed by some operations of addition, subtraction and multiplication, the straight lines (linear equations) that these tools represent also changes. After matrix, vector or scalar operations of addition, subtraction and multiplication performed by strict rules and methods, the initial linear equation changes to a new one. The operation of addition, subtraction and multiplication are like actions of washing, cutting, cooking, which are done by or on the tools of linear algebra, namely, matrices, vectors and scalars like knives, utensils, microwave, to manipulate linear equations like creating a new dish or new beverage from raw whole vegetables, or adding milk to coffee/tea or adding pepper to fish-n-chips. By studying how linear equations change i.e. their properties change, when their representations by tools matrices, vectors or scalars, are operated by multiplication, addition or subtraction, problems of linear equations or straight lines are solved. A linear equation problem typically involves finding values of unknown variables usually represented by letters x, y and z that satisfies a given set of conditions expressed in terms of those variables and some constant(s) usually represented by letter c. Solving the linear equation problem in linear algebra means determining unknown variable values based on the linear equation and constant(s), using the operations (multiplication, addition, subtraction) of tools (matrices, scalars, vectors).

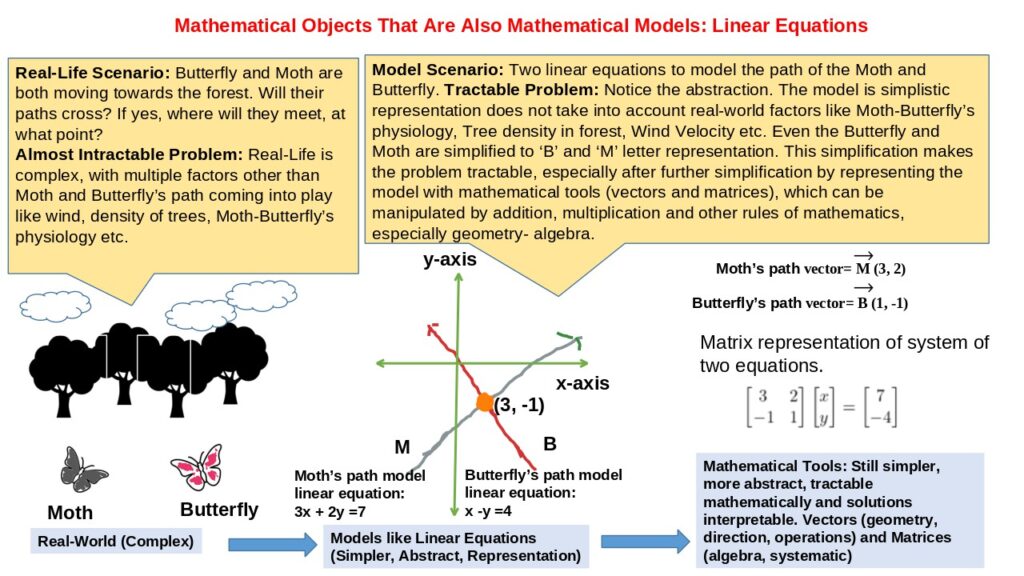

Lets look at an example of solving systems of linear equations with vectors and matrices – here the solution we seek to find is the point of intersection of two lines.

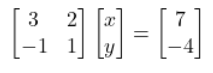

| Example 3.3. Solving systems of linear equations with vectors and matrices Scenario Being Modeled: –Moth is moving along Line 3x + 2y = 7. – Butterfly is moving along Line x – y = 4. Goal or Problem-Solving: Find out where these two lines intersect, meaning where they meet at the same point (x, y). This intersection point satisfies both equations simultaneously. Vector Representation: Each line can be represented by a vector that gives us direction and starting point. To get normal and direction vectors for each linear equation and the corresponding matrix, we can start by rewriting each equation in the form of the standard linear equation, ax + by = c, which is useful for identifying the normal vector (a, b). – For Line 3x + 2y = 7: We can think of the vector (3, 2) as representing how much to move in the x-direction for every unit moved in the y-direction. This vector can be combined with a constant vector (starting point) to create the full equation. – For Line x – y = 4: The vector (1, -1) represents moving 1 unit in the x-direction and -1 unit in the y-direction. Matrix Representation: To represent the two linear equations in matrix form, rule is that I need to express them as a single equation of the form ax + by = c. This is first time we encounter a rule in linear algebra, the ‘a’ can be – or +, but ‘b’ has to be +. – For Line 3x + 2y = 7: this can be written directly in the standard form. – For Line x – y = 4: I’ll rearrange it to match the structure of the first equation, so subtracting x and adding y on both sides gives x – y = 4 → x – y -x +y = 4 -x +y → 0 = 4 -x +y → -x + y = -4 Now, I can write both equations in matrix form by combining their coefficients: |

| This matrix representation clearly shows the coefficients of x and y, as well as the constants on each side of the equations. While vectors are more intuitive for geometric interpretation, matrices can be used to represent systems of equations or transformations between them. Now, in our case, we’ll focus on using substitution method of linear algebra or elementary algebra to find intersection of the two lines, because we have not yet discussed vector and matrix operations in this chapter. Linear Algebra or Elementary Algebra Solution: Substitution Method 1. From Line 3x + 2y = 7: “` y = (7/2) – (3/2)x “` 2. Substitute into x – y = 4: “` x – ((7/2) – (3/2)x) = 4 “` 3. Simplify and solve for x: “` x + (3/2)x = 4 + (7/2) (5/2)x = 15/2 x = 3 “` 4. Find y using the original line equation: “` y = (7/2) – (3/2)(3) y = (7/2) – (9/2) y = -1 “` So, the intersection point is (3, -1). |

In Example 3.3. we used vectors and matrices to represent lines and applying algebraic manipulation to solve for the unknowns, we determined where two moving entities (in this case, Butterfly and Moth moving along lines) will meet. This method leveraged the power of linear algebra to solve geometric problems systematically and accurately. Geometric Interpretation of why vectors work in linear equation problems, is that vectors naturally represent directions and distances, making it intuitive to visualize how lines move through space. Algebraic Interpretation of why matrix algebra works in linear equation problems, is that matrix operations provide a systematic way to handle multiple equations or transformations, ensuring accuracy in finding solutions.

3.4. Linear algebra is a cornerstone of mathematics with extensive applications across various fields.

Linear algebra has many applications in various fields such as physics, engineering, economics, computer science, and more. Linear algebra is important because it provides the foundation for many mathematical and computational techniques used in various fields such as machine learning, data analysis, computer graphics, control systems, signal processing, optimization problems, etc. Linear algebra is a powerful tool with applications across many disciplines. It provides a framework for modeling complex systems and solving various problems:

- Electrical Engineering: Linear algebra helps analyze electrical circuits, especially those with multiple resistors or sources. Concepts like series and parallel circuits use dot products in vector spaces to determine total resistance and current flow. Ohm’s Law, a fundamental equation in electrical engineering, relates voltage, current, and resistance. Linear algebra techniques are then used to solve systems of equations representing these circuits, enabling the design and analysis of complex electrical systems. (Cite: Book: Introduction to Linear Algebra with Applications, Chapter 2 by Jim DeFranza and Daniel Gagliardi )

- Chemistry/Environmental Science: In chemistry and environmental science, models facilitate estimation of distribution of microplastics pollutants and rusting of metals, and other uses. (Cite: Wu Q, Wang X, Xia P, Zhang X and Zhang R (2024) Editorial: Modeling for environmental pollution and change. Front. Environ. Sci. 12:1502134. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1502134; Cite: Tai McClellan Maaz, Ronald H. Heck, Christine Tallamy Glazer, Mitchell K. Loo, Johanie Rivera Zayas, Aleric Krenz, Tanner Beckstrom, Susan E. Crow, Jonathan L. Deenik,Measuring the immeasurable: A structural equation modeling approach to assessing soil health, Science of The Total Environment (Science Direct), Volume 870, 2023, 161900, ISSN 0048-9697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161900 )

- Biology: Linear recurrence relations are used to model population growth rates, and matrix methods are applied to analyze population dynamics over time. Disease progression models are helpful for both individual patients, as well as for large-scale pandemics. (Brice SN, Harper PR, Gartner D and Behrens DA (2023) Modeling disease progression and treatment pathways for depression jointly using agent based modeling and system dynamics. Front. Public Health 10:1011104. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1011104; Nikolaou, M. Revisiting the standard for modeling the spread of infectious diseases. Sci Rep 12, 7077 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10185-0)

The examples above show that linear algebra is a versatile tool that enables modeling, analysis, and optimization across a wide range of disciplines. It provides a common language for representing complex systems for study and solving problems, making it a fundamental concept in modern science and engineering.

###############To Be Continued#############